Bona de Mandiargues

16 May-4 Jul 2025

Alison Jacques presents a solo exhibition of work by Italian artist Bona de Mandiargues (b.Rome, 1926; d.Paris, 2000), curated by Simon Grant. In recent years, de Mandiargues has been the subject of renewed curatorial interest and international recognition, following her first institutional retrospective at the Nivola Museum in Sardinia (2022). In 2024, her work was included in the 60th Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Adriano Pedrosa and Surréalisme at Centre Pompidou, Paris.

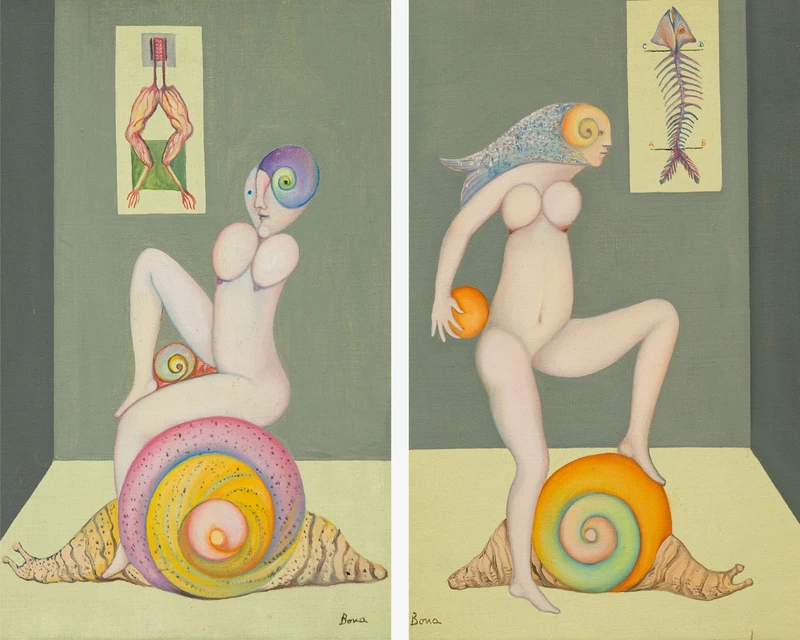

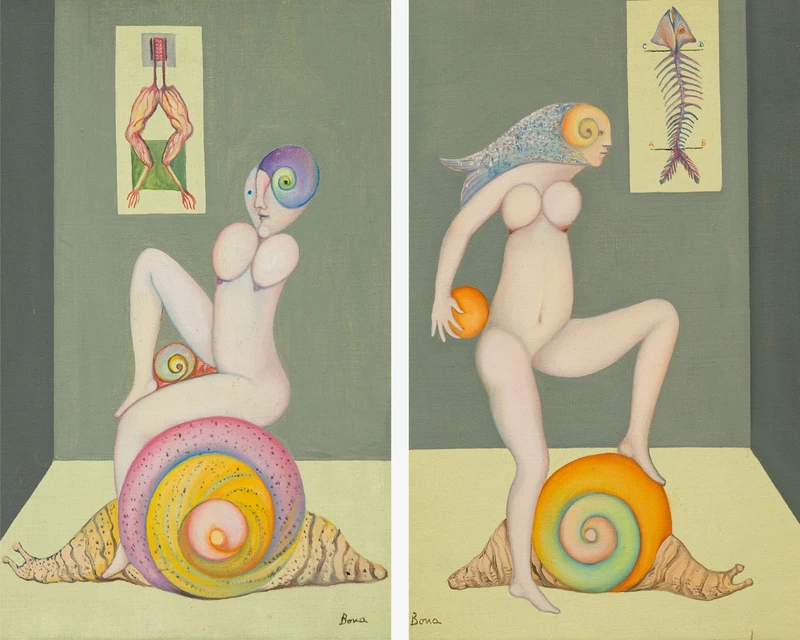

This exhibition, the first solo show of de Mandiargues in the UK, spans over 40 years of work, from 1951 to 1995, showcasing paintings and mixed media assemblages as well as colour pencil and gouache works on paper. De Mandiargues’s highly charged and surreal compositions reflect her intuitive, visceral, instinctive and often autobiographical approach. She created a powerful repertoire of work filled with figures of ambiguous sexual identity, fantastical creatures and images laden with symbols, mythology, metamorphosis and dreams.

Born Bona Tibertelli, the artist spent her childhood in a villa on a large estate in Emilia-Romagna near Modena, where she was drawn to places where she could lose herself: attics, cellars, stables, fields and orchards. After the death of her father, she moved to Venice to live with her uncle, the Italian painter Filippo de Pisis (b.1896; d.1956), who she described as a great influence and mentor, teaching her to use her ‘inner eye’. In Venice, de Mandiargues was introduced to influences she carried with her throughout her career; from the early Christian mosaics of Ravenna to Sienese paintings, and the work of Giorgio de Chirico.

In 1947 de Mandiargues made her first trip to Paris, where she met and later married the French writer and poet André Pieyre de Mandiargues (b.1909; d.1991), with whom she had a tumultuous relationship. Self-fashioning as ‘Bona’, she connected with key figures within surrealist circles, including André Breton, Max Ernst, Dorothea Tanning, Meret Oppenheim, Hans Bellmer, Leonor Fini, and Man Ray, who photographed her on several occasions. ‘Thanks to the Surrealist group’ she reflected, ‘I was able to see more clearly in myself what I had been trying to express.’

Bona travelled to Mexico with her husband in 1948. Crowned by Breton as ‘the most Surrealist country in the world’, Bona was inspired by the colours of Mexico, its pre-Columbian history, and local indigenous weaving, and entered a new artistic phase, abandoning paint in favour of fabric and collage.

Taking scissors to her husband’s old jackets, Bona ripped out and disassembled the linings, which Italian and French tailors refer to as l’anima and l’âme (soul). The resulting collaged and sewn fabric images — which she referred to as ‘ragarts’ — read like paintings, pieced together with a sewing machine and also by hand. ‘I chose these very humble materials…I flipped inside out the vests of men to get to the heart of their armour, of their protection.’ Bona regarded sewing, assembling and cutting as central to her art, stating that scissors were ‘as important to her work’ as brushes. In the assemblages, she creates an emotionally rich universe of threads and wefts, a process of making she described as ‘close to that of a witch working her spell’.

The act of destroying an established whole — in this case a man’s jacket — and reconstituting it, mirrored Bona’s desire to rebuild the world according to her vision. As she stated, ‘an artist’s first duty is loyalty to the material; the second is the process of its transformation, so that it becomes something more by not abandoning its nature.’ By physically stitching material, Bona sought to rip apart established Western binaries, chief among them the concept of male and female; the beautiful and the savage; the spiritual and the material, fusing them into a single form.

A central theme in this exhibition is the meaning of self, explored through the metaphor of the androgynous snail. Bona closely identified with this hermaphroditic animal, which she felt symbolised many of her preoccupations with opposites, contradictions, fragmented identity and sexuality. As she wrote: ‘Constantly torn by the desire to escape and the protective need to stay at home, I envied the privilege of the snail who can move around with his house. A lunar and moody animal, it symbolises movement within permanence. Perhaps because of this, I began to identify with him…By embracing the shapes of the spiral, I’m embracing the very structure of the universe.’