Robert Motherwell

11 May-24 Jun 2023

To celebrate Robert Motherwell’s lifetime achievement, Bernard Jacobson Gallery presents a three part exhibition starting May 11th, 2023.

The first exhibition will concentrate on his etchings, lithographs and screen prints. The second will be collages and drawings. The third will be paintings.

***

A letter from Bernard Jacobson:

To perhaps begin with ancient Egypt, moving forward to ancient Greece and Rome, we are fortunate enough to have considerable knowledge of how those societies lived through moments of happiness as well as times of strife and war.

New attitudes and discoveries leave us with a fairly clear picture of those times, on to Byzantium and up to the Renaissance, a period of a couple of centuries, the 14th and 15th, which some would see as virtually modern times, or at least fairly recent times. Which many of us will see as a long, long time ago.

The fog occasionally lifts as the winds of change allow us to see the vista as clearly as on a summer’s day. The artist of greatness will paint a picture or make a sculpture that responds to his or her own time, although the greatest of the greats, like Paul Cézanne, will paint the future, while having a clear summer’s day vision of the past.

Robert Motherwell had such a clear summer’s day vision of the past, the present and the future. His perspective was that vast. When I wanted to add Pierre Soulages, a great French painter of our times, to the list of artists to work for, I visited Paris to meet the French master in his immaculate studio, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame cathedral. In the quietness of his workplace we talked for hours, in a form of terrible French and terrible English. But we certainly understood each other. What truly bonded us, and what made Pierre put out his hand to shake on the arrangement, was hearing of my great passion for the American painter Motherwell, at which Pierre exclaimed in awe, “Ah, Muzzerwell!

And what inspired Soulages to return to his studios, in Paris and Sète, every day was his profound love and belief in Medieval art. For Motherwell it was his passion for all times. When you have Motherwell’s lifetime’s work in focus, the whole story, from the early forties till his death in 1991, you see the lifetime’s achievements of a great man and a great artist, one who towers above his colleagues and the artists of his time.

For us in the West, artists from Cimabue to Robert Motherwell and perhaps onwards in time, set the pace, set the standards and most significantly led the path forwards from a reasonably clear road from post Byzantine culture, through Italy’s Renaissance, to be taken up and developed by France in the 18th 19th and early 20th century until the rumblings of a world war in the late 1930s shifted the focus from Europe to Manhattan.

A relatively small band of brothers, led by Robert Motherwell himself and others, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman, Willem de Kooning, Clifford Still, had a deep desire to make an American art that could take on Picasso, Braque and Matisse and the whole idea of the Ecole de Paris.

In many respects they achieved that ambition and won the day! Their huge canvases of drama and power did in some ways dwarf what was being painted in Paris.

In so many ways they were like-minded souls in their intent, although with extremely differing visions. But some aesthetic glue did bond them together, filled with anger and frustration, with ambitions for a new vision.

It seems fairly clear to me that the odd-man-out was Robert Motherwell. For superficial reasons on the one hand – he was from money and was definitely middle class. His father, a cultivated man, was president of Wells Fargo Bank in California. The young man went to Stanford, then Harvard and eventually on to Columbia. Most of the other painters in the gang were far more angry and from less grand backgrounds. They were all older than him, although it was he who had the intellectual staying power. Pollock was the regular at the Cedar bar and would all too often drink far too much and get into brawls. Motherwell stayed at home writing and editing, which would irritate his dealer Sam Kootz. It must have been a bit annoying, having this tall and elegant Californian, a decade younger than some of them, telling them what they were trying to achieve. In fact, it was Motherwell who, thinking Abstract Expressionism was not a broad enough term, named it, more accurately, The New York School.

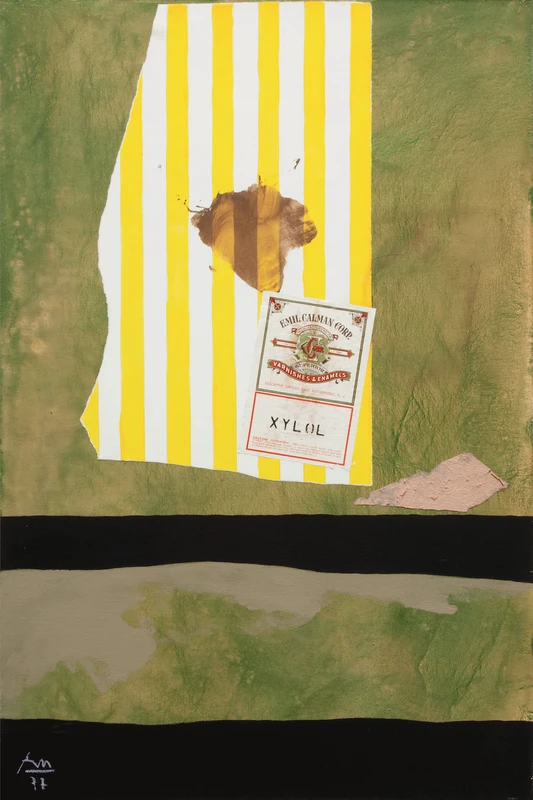

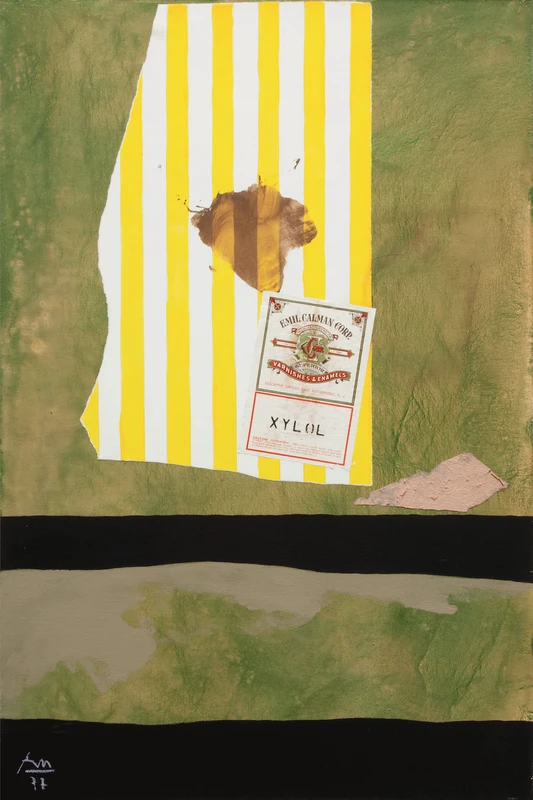

But a more significant reason why he was the odd-man-out was, while they wanted to make a split from current Paris art, it was Motherwell who believed in the greatness of the Parisian artists – he lived and exhibited there in 1938 - and their gigantic addition to the ongoing story of art. He simply continued the story. As much as he had, as a young man, learned so much from his good friend Mark Rothko, he also learned equally as much from the work of Georges Braque, when he fell in love with the Frenchman’s inventions of Cubism and also Papier Collé, the collage, so much so that he brought the relatively new technique of collage to America and over the decades produced more than 800 of them from 1943 until the end of his life, often on a much larger scale. Also, when you look carefully at one of the famous large bird paintings by Braque from the 1957, it does look very much like Motherwell’s Elegy image. Except that he had made the first Elegy in 1948! But the point is he is not merely an American rebel but an artist of world class and stature. I truly believe that this artist has the exceptionally rare status to join the small elite continuing and adding to the story of world art, not just on an international but also a universal and timeless level. A giant of art.

Another thing that separates Motherwell out was the vast programme he was working on. Not only did he develop and reinvent constantly, from the first collages through the great moment of the Elegy to the Spanish Republic series, the Open paintings, to the smaller although no less significant series such as Beside the Sea, The Lyric Suite, and at the end of his life The Hollow Men series. Plus 500 great and explorative and beautiful etchings, lithographs and screen prints. And another aspect was that Motherwell was a true intellectual – he produced endless essays and commentaries, he edited and wrote and translated extensive texts on Surrealism, Automatism, Duchamp. Some saw him as merely an academic who also made paintings. How wrong they were!

I can be extremely fond of minor artists. For instance I love the paintings of Giorgio Morandi, Peter Blake and Wayne Thiebaud. But Motherwell didn’t set himself up to be a minor artist. He sought the grand canvas, in every sense of the word. He hadn’t made great sacrifices in life to become just a very good artist. It was his tutor at Columbia, Meyer Schapiro, who realised that he wasn’t really interested in academia in the art world. He searched for the grand tradition. He found it! Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock and the others had the same ambitions as him, but I personally don’t think were able to achieve theirs to the same extent. His great mind and stamina would not let him down. He would not disappoint Schapiro, or us!

Nobody in their right mind would attempt to read our future on this planet. But even if there is a huge shift of power in the world’s culture, I believe that the works by Motherwell will remain of relevance to the world and his friend Jackson Pollock may have to become merely the great American hero, which is no small thing anyway.

The beauty and the power of a Ming vase or a Benin Bronze or a mysterious sculpture of Buddha may sit comfortably with a majestic Elegy or an expansive Open painting.

As we get nearer and nearer to a new tomorrow, future generations won’t know or care about Jackson Pollock’s antics of getting drunk at the Cedar bar or urinating in Peggy Guggenheim’s fireplace or being killed while drunken driving through the Hamptons. It will simply be the painting in front of the eyes of the people that will count.

The other day I bought a small painting by Georges Braque from 1918. It wasn’t simply the beauty of that tiny canvas that counted. It was for me also the knowledge that Andre Gide had owned that painting and he had it in his study for decades. And it was the genius of Gide that uttered the words, “It is time for relearning.” or, more importantly, “Please do not understand me too quickly.” I am completely confident that Motherwell would have fully understood the deep significance of these few words.

“If you want to discover new lands you must first have the courage to lose sight of familiar shores.”

“This unlearning was slow and difficult. It was of more use to me than all the learning imposed by men, and was really the beginning of an education.”

- Andre Gide

I am constantly so excited and proud to exhibit the works of Robert Motherwell, in all the media he embraced with great skill and perfection and depth. He has all the flair of Picasso, the profundity of Braque and the colour of Matisse. Nearly ten years ago I wrote a book on this wonderful artist and I stand by every word I wrote. It is just that, now hopefully a little wiser, I think he is even greater and especially now more relevant.

Yours,

Bernard Jacobson